If someone tells you that they experienced jazz and baseball on their trip, would you be able to correctly identify the country? If you guessed the U.S., try again!

I am talking about Japan.

The Japanese are crazy about jazz and baseball. The American presence in Japan following WWII left an undeniable mark on the country, and Japan has adopted and embraced these two very American things as its own. Fascinated with this cultural phenomenon, we decided to get to know Japanese jazz and baseball in Tokyo.

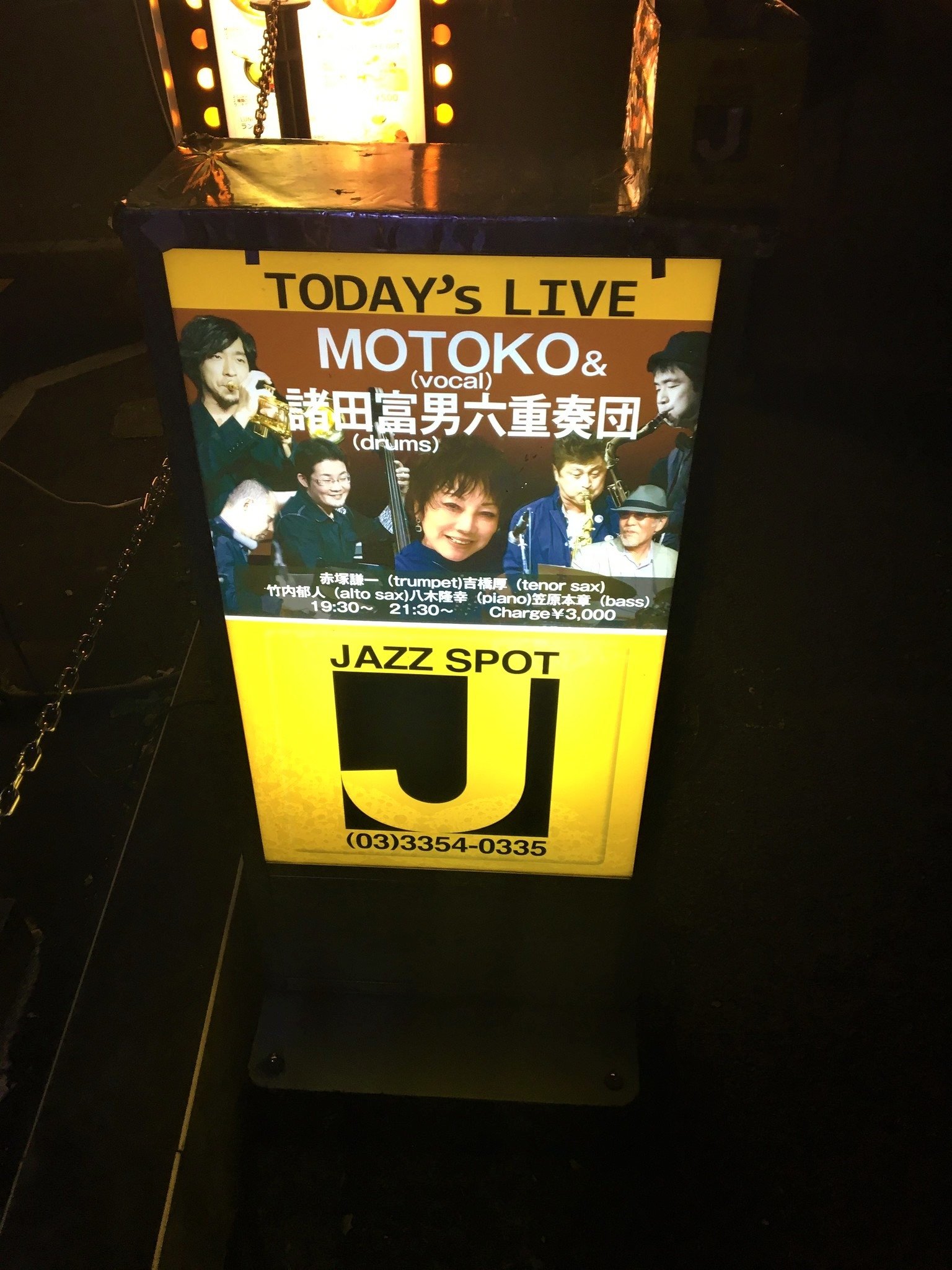

Tokyo boasts a number of jazz clubs. Initially, I wanted to go to Blue Note-Tokyo. After all, Blue Note in New York City is one of the best (if not the best) jazz clubs in the world, and it never disappoints every time we go there. So, Blue Note-Tokyo was a safe bet. Yet, when we found out that the admission price for that night to Blue Note was a whopping $80 per person (that’s right, Japan is expensive), Julia immediately shut down the idea and asked to find something cheaper. I quickly found another jazz club, Jazz Spot, and we headed there for the night out.

Finding the venue was a challenge. As we were navigating the unfamiliar streets of Tokyo, GPS on our phones kept stubbornly pointing to a nondescript building insisting that the jazz club was located there. Yet, as we were standing where the club was supposed to be, we saw absolutely no possible entrances to the club. The jazz club’s sign, which we spotted only after desperately examining the building for several minutes, was so tiny that it was no wonder we couldn’t find the entrance. We entered a plain door that led to another door, and then took stairs down to yet another door. It felt as if we were looking for a speakeasy in Chicago in the 1930s. Finally, after opening the last door, we found our way to a dimly lit intimate jazz club, where musicians were setting up their instruments and patrons were getting comfortable in their seats.

Immediately upon entering, we became the center of attention. All patrons and musicians were Japanese, with no other foreigners in sight. We certainly stood out and people were looking at us with a certain fascination. After we sat down in the corner, a man at the next table leaned over and asked us in very bad English where we were from. Hearing that we were from the U.S., people around us started buzzing with some weird admiration and approval. The musicians were also intrigued by our presence. During the set, as they were performing, they were constantly looking at us, as if seeking validation. I wanted to tell everyone that we were just two random tourists and not the executives of the Jazz Foundation of America auditing the quality of Japanese jazz.

Never having heard Japanese jazz before, we weren’t expecting much. We've been to some terrible performances in the U.S. and didn’t know what exactly was going to happen here, thousands of miles from jazz’s birthplace. Fortunately, the music was fine that night and we thoroughly enjoyed ourselves. After the set was over, we got up from our table and started making our way out. The musicians and patrons were a bit upset seeing us leave and even asked us if we liked the music. We complimented the performance but said that we had an early start the next day and needed to head home.

We were lucky to attend a live jazz performance in Tokyo, but, unfortunately, it was too late in the year for a baseball game. Still, eager to learn about Japanese baseball, we went to the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. The Hall of Fame is housed in Tokyo Dome, home of the Yomiuri Giants, the most successful baseball franchise in Japan and Japan’s equivalent of the Yankees. The Hall of Fame has several rooms presenting the history of the game in Japan, from the origins of its export from the U.S. to subsequent popularization following WWII. The museum displays various memorabilia, including baseballs signed by notable players, uniforms of various teams, and rare baseball cards.

As with every Hall of Fame, the most sacred room is the one dedicated to the inductees. I spent most of my time in this room, studying plaques depicting members of the Japanese Hall of Fame with descriptions of their contribution to the game. As I was going from plaque to plaque, I had to suddenly stop in my tracks. The player inducted into the Japanese Hall of Fame had my first name? But “Victor” is not a Japanese name. The player was clearly Russian, although his last name “Starffin” was neither Japanese nor Russian. His birth name (Viktor Konstantinovich Starukhin) was also written in Russian on the plaque. Immediately, I got intrigued. Japan had a Russian player, and not just any player but someone who got inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame? The plaque under the name did not provide much information. It simply stated:

Starffin, Victor

“Successor of Sawamura in the first heyday of the Tokyo Giants in pre-war pro baseball. Won 42 games in 1939. After the war, the White Russian played in the Pacific League, becoming the first 300 winner in 1955.”

I was desperately looking around, trying to find some explanation, but there was no one I could ask about Victor Starffin. After I finished with the visit and got connected to WiFi at a nearby cafe, I immediately Googled his name. Victor Starffin’s life story reads like a script of a thriller worthy of Hollywood directors. If you want to read a fascinating life story with plenty of plot twists, look him up. Born in Russia, Victor Starffin grew up in Japan, where his parents fled following the Russian Revolution. Life in the new country was full of drama for the Starffin family. At some point, Victor’s father killed his young Russian mistress, initially claiming that he did it because of jealousy but then changed his story claiming that she was a Russian spy!

As his father was awaiting trial on charges of involuntary manslaughter, Victor was a star high school baseball player and was scouted to join the national baseball team for an exhibition game against the U.S. At the time, the Ministry of Education had a rule that high school baseball players who played professionally were not eligible to enter higher education. Victor wanted to attend Waseda University and was understandably reluctant to turn pro. Matsutarō Shōriki, the Japanese media mogul and father of Japanese professional baseball, effectively blackmailed Victor, threatening that if he refused to play professionally, Shoriki would use his connections to publicize the details of his father’s criminal case, which could cause the family to lose their visas and get deported back to Russia.

Victor joined the national team and ended up playing against some of the best players in the world, including Babe Ruth in 1934. Considered to be one of the best players in the Japanese baseball league, Starffin, also known as “the blue-eyed Japanese”, went on to become the first Japanese player to win 300 games. He was also one of the first inductees into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in 1960, shortly after his tragic and somewhat mysterious death in 1957 at the age of 40. One can only wonder what his life could have been had his parents stayed in Russia.

There will be other posts where we describe just how different Japan is from the U.S. and the rest of the world. We found so many basic things to be unique in Japan, not just cultural norms, but food, transportation, housing, and clothes. We didn’t know why the streets didn’t have garbage cans or how to sleep on tatami mats, or where to line up for the trains, or even how to properly eat Udon soup. But in our very first introductory post about Japan, we wanted to share a little glimpse into what we found to be so comfortingly same, so far away from home.

This is the last entry for this year and the last time we will be posting before our big end-of-year trip to Vietnam. Happy Holidays to everyone and we’ll see you next year!