The train arrived at 3 a.m. We descended from the passenger railroad car, groggy and disheveled, into a dimly lit platform, the edges of which were swallowed by the night. Kolya, our team captain, silently motioned, and we marched down the platform behind him. I was 19 years old, and I was ready to conquer Donetsk. Just to clarify – my college comedy team and I were getting ready to perform at the Donetsk international comedy competition in March of 2002.

Now, exactly twenty years later, it barely seems real. Was I really there, walking the streets that would later get bombed, entertaining audiences from the stage, some of whom would be displaced or perish from the atrocities of the upcoming war?

But I am getting ahead of myself. Back then, I was not the traveler I am now but had all the inklings of becoming one. This was only my second trip to Ukraine, the first being a family vacation to Odesa a few years before, and I was excited to explore new lands. Even though sunrise was still an hour away, I dragged my teammates out of our hotel, aptly named Shahtar (“Coal Miner”) for Donetsk is in the heart of the mining region, and towards the city center. We walked the dark, empty streets, climbing on monuments, posing in front of statues, laughing loudly for no reason – all the types of hijinks unsupervised college students can get into in a new city. The street signs adorned with the yellow-blue colors of the Ukrainian flag greeted us with, “Glory to Donbas.” As the first rays of sunlight flickered through the darkness of the horizon, we suddenly could see majestic slag heaps rising out of the dusk around the city. These giant hills of rock and mud, leftover waste from industrial mining, surrounded us and towered next to every coal mining site. Noticing a few slag heaps in the vicinity of the soccer stadium, also named Coal Miner, we immediately came up with a new joke for the comedy competition. A week later, Kolya, dressed as a Coal Miner fan (yes, the soccer team was also named Coal Miner), yelled, “May you only afford to watch the games from a slag heap!” and the audience roared in laughter. It turned out that people did, in fact, watch games from slag heaps, and this was our best joke of the game.

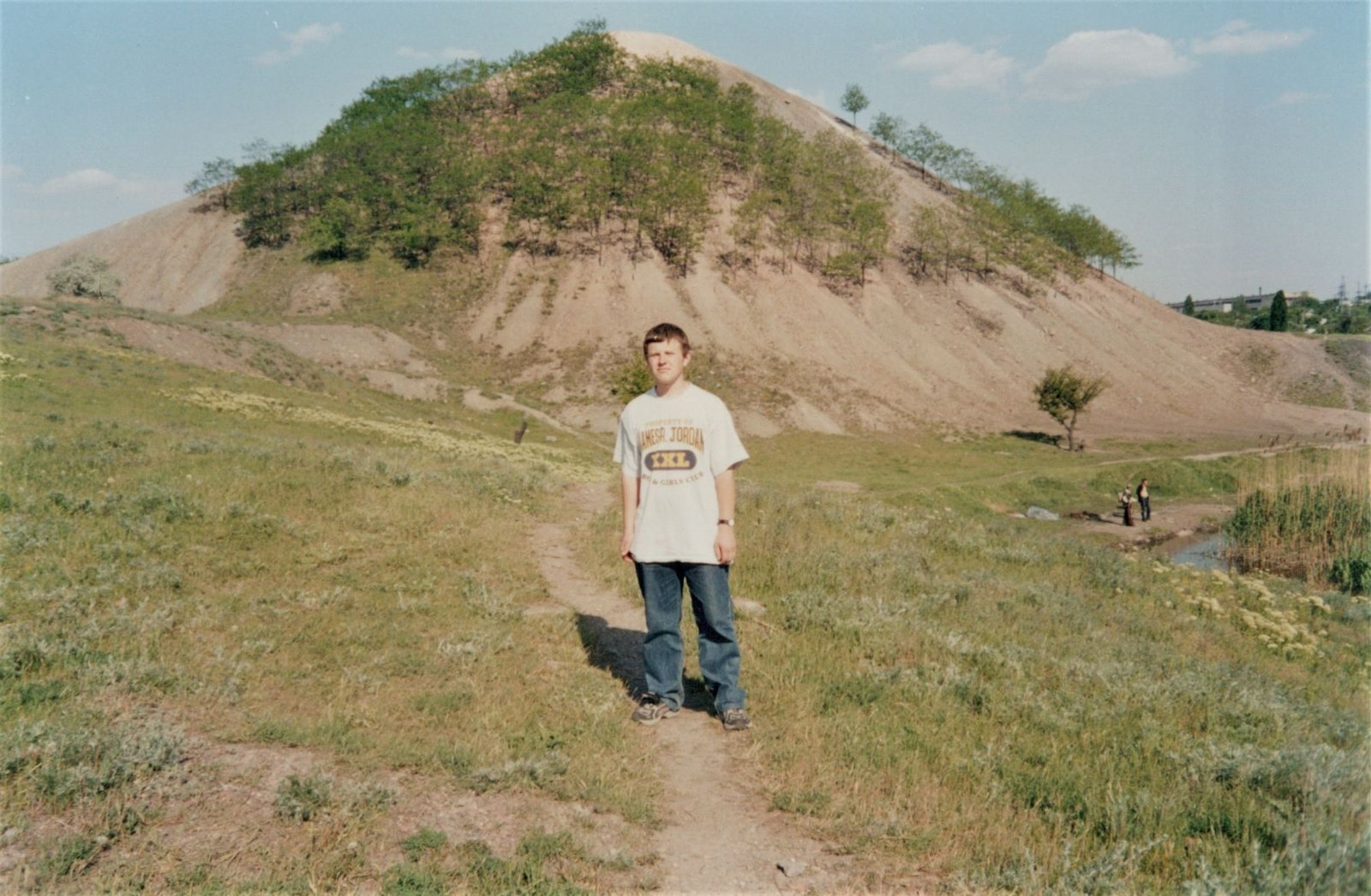

Slag heaps, as strange as it sounds, were the most recognizable landmarks of Donetsk. Looking more like Egyptian pyramids than industrial waste, they were prominent throughout the city and surrounding areas. I went as far as climbing one and only made it halfway in half an hour, before giving up and skittering back down. It was clear from all the slag heaps why every other hotel, restaurant, and business was named “Coal Miner”.

While Donetsk itself looked like a typical post-Soviet city with housing blocks, wide avenues, and parks, the surrounding Donbas region did have a bit more ethnic flavor. At one of the station stops, I looked outside of the train window and saw traditional Ukrainian village houses called mazanky, named so for the white limewash wall paint. Framed by distant slag hills, these cute little houses with wooden wicker fences looked like time travelers from a not-so-distant pre-revolutionary past. I could not see it from my train window, but there were certainly clay and cast-iron pots (banyaki) hung upside down drying on these fences, per the Ukrainian customs. During my first year in Chicago, I even heard stories that early Ukrainian immigrants in Chicago were called banyaki for doing exactly that, using fences in the Ukrainian Village in Chicago to dry and store pots. Although a lot has been speculated about Donbas being more Russian than Ukrainian, the most Ukrainian landscape I saw in my life was at that train stop somewhere in Donbas, an hour outside of Donetsk.

The next day, we performed in front of the competition producers, who were very generous with their evaluation of our script. They ended up accepting our entire performance the way it was, meaning we didn’t have to rewrite and re-rehearse any part of our routine and were ready for game day, five days from now. That’s five free days in Ukraine, and I was ready to take full advantage.

“I want to go to the Azov Sea,” I told one of the game organizers. “How do I get there?”

“Mariupol is your best bet,” he told me, writing down the number of the minibus that was leaving for Mariupol every few hours, “But it’s not a beach town! You won’t be able to swim. You will see plenty of sea and a nice port town.”

I don’t remember why I never made it to that minibus or Mariupol. Maybe the locals I talked to were dismissive of Mariupol’s ability to draw tourists’ attention, or maybe my teammates kept pulling me into drinking, parties, and various pre-game preparation activities. Maybe I simply wasn’t the traveler I am today.

I did get a glimpse of the Mariupol soccer team when I attended FC Mariupol “Steel Worker” vs FC Donetsk “Steel Worker” game… at the other Donetsk soccer stadium named… “Steel Worker”. The industrial nature of Donbas was only further highlighted by the fact that if something was not called a “Coal Miner”, it was a “Steel Worker”. Back in 2002, I was vaguely aware of the fact that the Mariupol “Steel Worker” soccer team represented the Azov steel plant, the plant that the entire world would know as a symbol of Ukrainian bravery and fight for freedom twenty years later.

We traveled back to Donetsk three more times that year, for the quarterfinal, semifinal, and final. I got used to slag heaps, living off cheap and delicious pizza-like flatbreads sold in street food stalls all over Donetsk, and the fascinating way locals had of answering Russian questions in Ukrainian and vice versa. I made local friends, visited my relatives in nearby Gorlivka, drank more than I ever should have, and never made it to Mariupol.

Twelve years later, when the Donbas War broke out, I contacted everyone I still remembered. They all evacuated to Russia or other parts of Ukraine. And now, twenty years since my visits to Donbas, Mariupol has been reduced to rubble, snipers are stationed on top of slag heaps, and the entirety of Ukraine is in the fight of their lives for the survival of their country.

Each of us has a dream of what Ukraine should be like, and mine is that distant memory of Donbas of my youth. If you are able, please pick a charity involved in humanitarian relief, recovery, and peace-building efforts in Ukraine and donate towards the Ukrainian dream.