We have mentioned in this blog that we don’t drink alcohol unless we travel. No, it’s not a complicated loophole in a mostly sober lifestyle; we are simply submerging ourselves in cultural explorations. We firmly believe that learning about the drinking culture of a country can help us get a glimpse into the country’s psyche, culture, and traditions. Albania was not an exception.

As we were getting ready for the trip, however, I did almost no research into the drinking culture of Albania. Albania is a Muslim country after all, and I assumed (wrongly) that we were unlikely to experience any drinking culture there. For some reason, I imagined Egypt or Jordan where you can find alcohol only in Western bars and served only to foreigners. So, when on our first night in Tirana we stumbled into hundreds of young people in the Skanderbeg square drinking beer and loudly cheering on soccer teams of Euro 2020, I immediately knew that something was off. This was not your typical Muslim country. As we described in our last post, Albania had a very rough 50-year stretch of history under the Communists when religion was totally banned. As a result, Albania nowadays is only nominally Muslim, lacking the stringent constraints of Muslim conservatism. People rarely, if at all, attend mosques, women drive and wear miniskirts and shorts, while drinking and smoking appear to be a national pastime. As we walked among tipsy and boisterous Albanians, I wondered how Muslim tourists from more religious and conservative countries react when they get to Albania. Are they repulsed by what they see? Do they even consider Albanians proper Muslims?

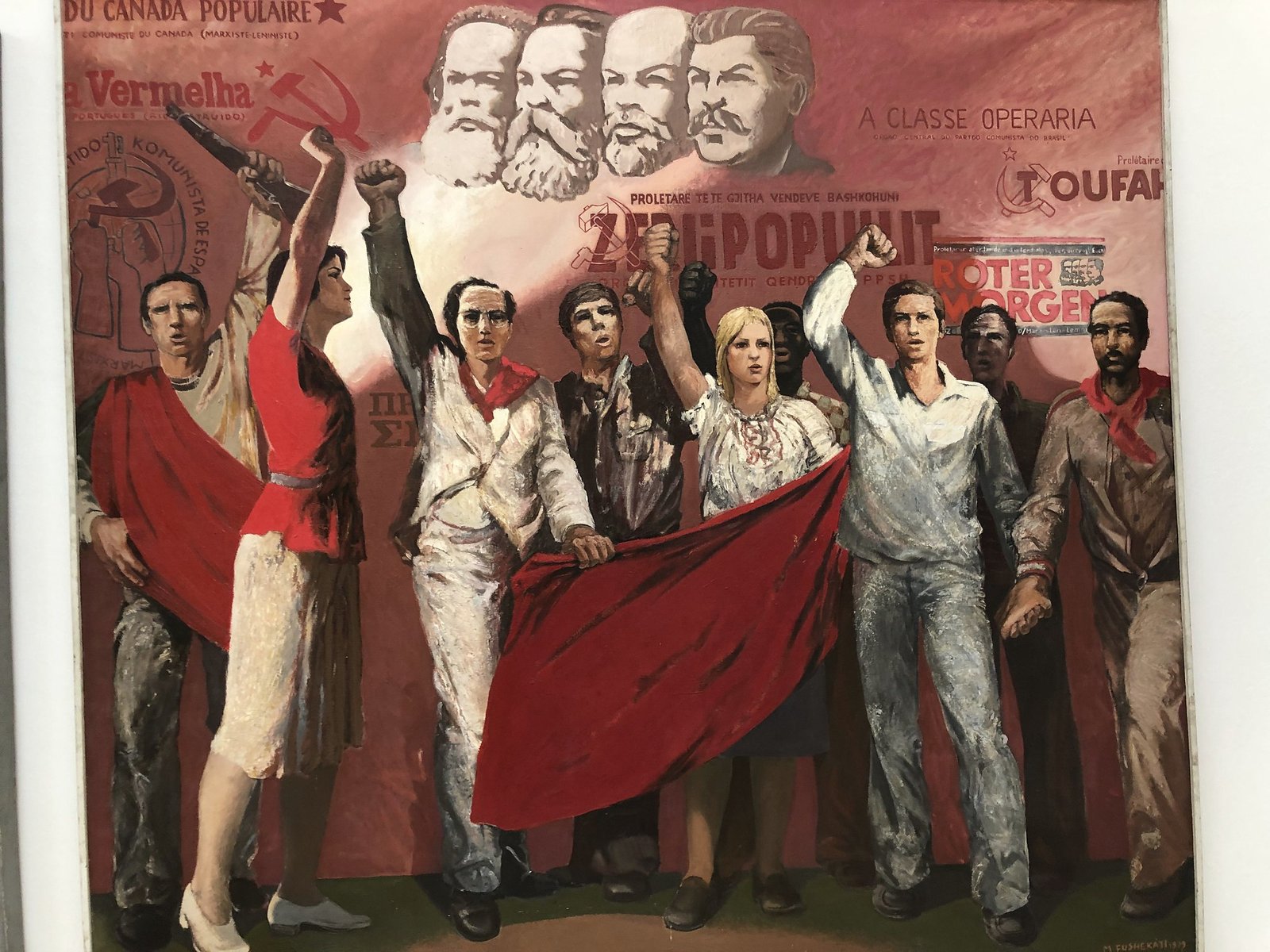

We had no qualms with the country’s liberal take on Islam. On the second night in Tirana, we joined the fray by going back to the Skanderbeg square to watch the England-Scotland match on a giant TV screen in the fan zone. Hundreds of young people drinking Korça and Tirana beer were loudly cheering for England. At halftime, the TV was muted, and the place was overtaken by a showy DJ mixing and blending the sounds of popular dance music, turning the entire fan zone into one huge open-air nightclub. The place had a feel of a party beach in Ibiza rather than a central square of a Muslim country with a Communist past. While being in the vortex of the partying and surrounded by happily inebriated young Albanians, I couldn’t help but look around. Our surroundings were puzzling. The building of the National Museum of History adorned with a massive Communist-theme mosaic stood in the farthest corner of the square in the dark, looking down at the ongoing bacchanalia with silent disapproval. On the other opposite side of the square, a minaret of an old mosque loomed so lonely and so out of place. Our first two days in the Albanian capital showed us that the times have changed. Today’s Albania is no longer restrained by the shackles of Communism preventing people from enjoying their lives. Nor does it retain the religious limitations that are still prevalent in other more conservative Muslim countries. Young people drink beer and enjoy themselves as much as their counterparts in other European countries. And good for them.

As we continued our travel through Albania, we quickly found out that the drink that rules Albania (and the Balkans) is raki or rakija, a spirit distilled from pomace that is leftover from winemaking after the grapes or fruit are pressed for juice. The drink is quite popular and is known by other names in other countries. For example, it is chacha in Georgia and grappa in Italy. Albania’s raki is special as it also can be made of plums, walnuts, and mulberry. The choices are boundless and Albanians, it seems, can make delicious raki out of everything. When we arrived in Berat for our two-day stay, our hosts, a lovely married couple in their early 40s, greeted us with shots of homemade orange raki which was the best raki we tried in Albania. They explained that Albanians usually make raki for personal consumption, not for sale, and that all their neighbors make their own raki with each family utilizing its own secret recipe or technology. When we asked them about their secret sauce, the husband told us that he was using a high-quality home distiller that he bought in Italy for 300 euros. He then went downstairs and proudly brought back a shiny copper home distiller. After spending two wonderful days in Berat that involved not only exploring the striking architecture of this historic Ottoman town but also connecting with our hosts on a personal level, we received a parting gift of a bottle of orange raki - the best souvenir we brought back home.

Drinking raki is an indispensable aspect of daily life in Albania and somewhat of a ritual. It is a common sight, from up north in the Albanian Alps and down in the south in Albanian Riviera, to see men sitting in coffee shops or bars sipping raki with potent Albanian coffee and smoking a cigarette. That’s how daily news is discussed, deals are made, and even marriages are arranged. The Albanians have yet to receive a memo on how to lead a healthier lifestyle, but with globalization and young people being more exposed to Western values, the days of the tradition of drinking raki in the morning, afternoon, and dinner may be numbered. Another aspect of the raki drinking ritual is that women were conspicuously absent from these gatherings. While I have the greatest respect for local customs, I was traveling with three women and was not about to drink alone. And that’s the story for the next post – how I managed to get my mother, aunt, and Julia completely wasted on raki.

Coming up Next Week: Our visit to an Albanian family winery, where my family got drunk.