“So, did we travel internationally or not?”

We asked ourselves this question recently after returning from the U.S. Virgin Islands. Before the trip, we felt we weren’t traveling outside of the United States. The USVI is not a country. It’s a territory and part of the United States. The “U.S.” is in the name, and its flag is just a modified version of the U.S. coat of arms. No passports or visas were required. We just hopped on the plane and went.

But the islands didn’t feel like anything mainland U.S. Sure, people spoke English, and most tourists were from the U.S. The supermarkets were stocked with American goods, and trails in the Virgin Islands National Park were well marked—as they usually are in U.S. national parks. Yet, there were so many things that made us feel we were in a foreign country.

Driving on the Left

This is the most “un-American” thing we encountered in the Virgin Islands. Before the U.S. purchased the islands in 1917, they had been under Danish rule, and driving on the left was adopted as the prevailing European practice. Once the islands became U.S. territory, the U.S. decided not to mess with the existing traffic patterns, and left-hand driving stayed.

This may come as a shock to some Americans who travel to the USVI and plan on renting a car there.

Having done no prior research into the local driving culture, Julia was wide-eyed when we left the airport’s car rental office, and I started driving on the “wrong” side of the road.

“Are you sure about this?” she said, watching the oncoming traffic nervously.

Driving on the left wasn’t hard for me, as I previously drove in England and Ireland. But there was a local quirk—the cars were designed for driving on the right, so the steering wheel was on the left. Why? Probably, because most cars are brought to the islands from the mainland U.S. But honestly, I did not mind. The roads in the USVI are very narrow and steep, and you often drive along cliffs, so it actually helped to sit on the left and know exactly where the edge was.

Danish History

Those who travel through the continental United States can encounter traces and influences from other countries—England, France, Spain. But Denmark? Other than delicious kringles from Racine, Wisconsin, where a lot of Danish immigrants had settled, we haven’t found much of the Danish influence anywhere in the U.S. Until we came to the Virgin Islands. Although the U.S. purchased the islands more than 100 years ago, the Danish heritage is still visible there.

Driving on the Main Street in Charlotte Amalie, the capital of the USVI, we were scanning street names searching for our Airbnb. The names were Danish, and each street sign had one word in common—“gade”. Later, we learned that “gade” was “street” in Danish: Dronningens Gade (“Queen’s Street”), Kongens Gade (“King’s Street”), Prindsens Gade (“Prince’s Street”).

But Danish influence wasn’t only in the names but also in the architectural style. The town center was full of typical Danish colonial architecture with stately colonial buildings, mansions, and defensive towers. Our Airbnb at Snegle Gade 6, for example, was in an imposing three-story colonial townhome with wide decorative enframements, outer shutters, and a cast-iron balcony.

Beaches

I know, I know. The continental U.S. has great beaches, too. Florida and California have their share of inviting stretches of sand by the water. But nothing truly compares to the heavenly Virgin Islands beaches. In just six short days, we visited seven beaches on Saint Thomas and Saint John, and each—no exception—was postcard-pretty. Beaches are the main reason why people travel there, and it’s not difficult to see why. White sand and teal blue water, the beaches are unmistakably Caribbean and easily beat any beach we’ve ever visited on the mainland.

Sugar Mill Ruins

What also makes the Virgin Islands distinctly Caribbean are the ruins of former sugar mills. Like in so many places in the Caribbean, sugar production once dominated the local economy. Relying on slave labor, the local mills churned out prized sugar loaves that were later shipped out of the islands to the world’s markets. The fall of the sugar trade here almost mirrors what happened at other nearby destinations at the end of the 19th century. Slave revolts, the Industrial Revolution, and an increased reliance on sugar made from European beets caused the Caribbean sugar production to collapse.

Hiking through the U.S. Virgin Islands National Park on Saint John, we came across numerous abandoned sugar mills. The atmospheric ruins were in different stages of decay and looked very much like the ruins of sugar production in Cuba's Valle de los Ingenios that we visited several years ago.

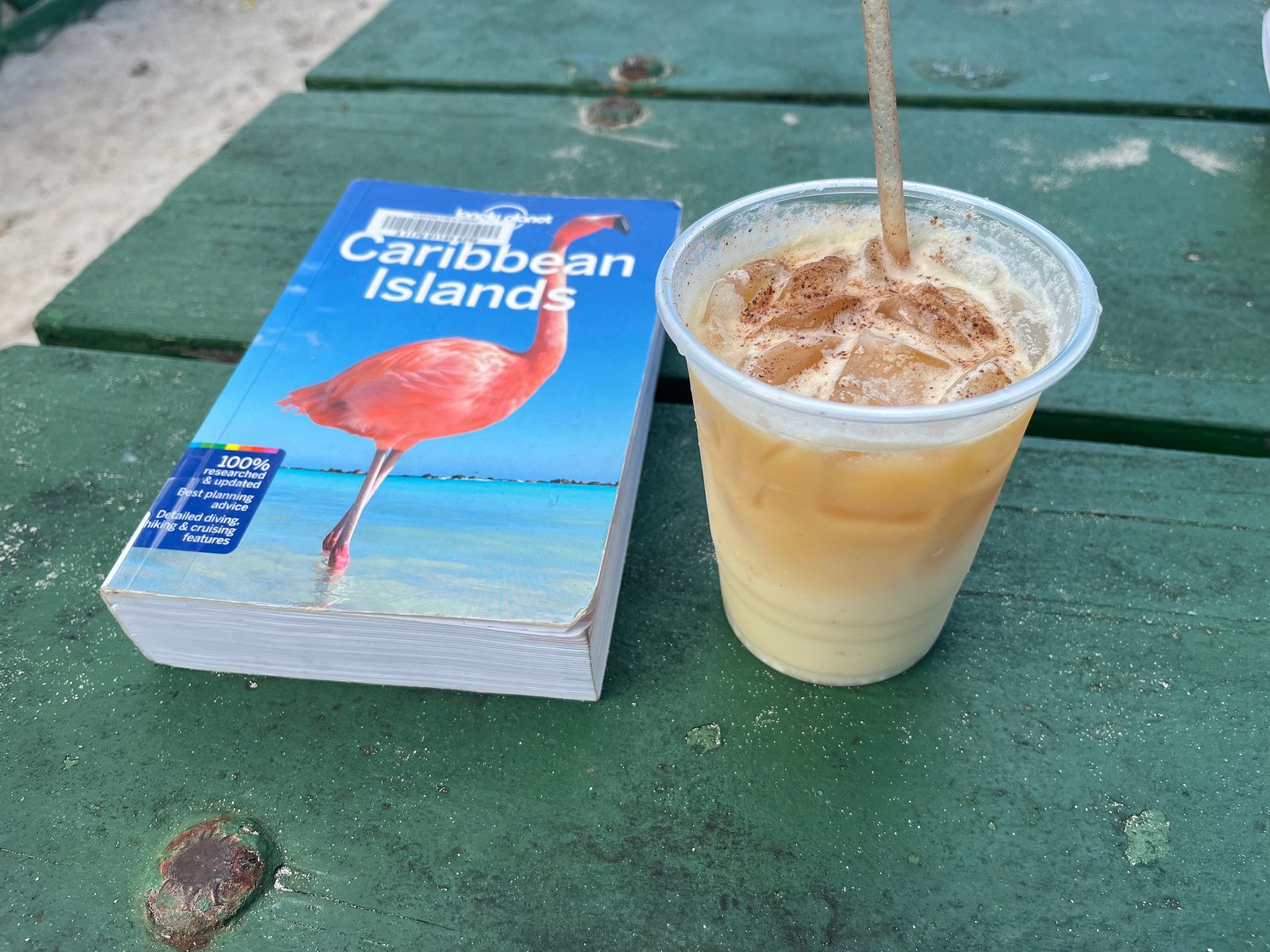

Painkillers

When I told Julia that I wanted to try painkillers in the Virgin Islands, she just had to ask:

“Why? And are you ok?”

I know what you’re thinking. You can get painkillers in the States. No need to travel somewhere to get them.

But in the Virgin Islands, a painkiller means something else—a popular tropical cocktail.

Even though it originated in the neighboring British Virgin Islands, it’s the drink of the USVI. The recipe is quintessentially Caribbean: ice cubes, dark rum, coconut cream, pineapple juice, orange juice, and freshly grated nutmeg sprinkled for garnish. The drink reminded us of a piña colada, but it was more refreshing, fruitier, and spicier.

We’re not big drinkers, and maybe Painkiller cocktails can also be found at some tiki bars in the United States, but it was the USVI where we encountered it for the first time, and where it’s a hit with the locals and the visitors.

Flying back to Chicago, we snacked on pastries purchased at a local bakery on the way to the airport. The baked goodies were less sweet and more dense, just different enough from the pastries on the mainland, and that encapsulated this entire trip. Even though the U.S. Virgin Islands are part of the United States and have many things in common with the continental U.S., they have their own flavor and taste different.