We want to travel the world. As in - the entire world. But reasonably, of course, we don’t have the time or the money or the inclination to truly travel the whole world. There are plenty of countries which are too dangerous or too expensive or too unaccommodating for travelers. Besides, we have an extensive list of dream destinations we need to get to first. India was never on that list for me. Honestly, it was edging closer to “too dangerous right now, we’ll get to it if we get to it” countries. There were plenty of stories in the news about Western women being raped on public transportation – buses, taxis, trains, even when accompanied by a male. There were too many stories of inhumane poverty, slums, and beggar children. And way too many stories of food poisoning and diarrhea afflicting every Westerner who dared to eat or drink anything during their stay. Until suddenly, it was on our list.

It happened while we were in Egypt, on an overnight train, going from Aswan to Cairo. We booked first-class tickets in a sleeping car because our guide, Mohammed, insisted it would be too loud and uncomfortable in the general class, and tickets to the first class were easily affordable. As we got on the train and found all individual sleeping compartments packed exclusively with tourists, I felt a twinge of regret. It would have been nice to travel among the Egyptians, meet some locals, and learn a bit more about the culture. But instead, we were meeting fellow travelers – two twenty-something Ukrainian girls and an Englishman in his late forties. The Ukrainian girls were full of life, optimism, and complete disregard for personal safety that comes with being young and naïve. They babbled on and on about disregarding Egyptian government orders that tourists were only allowed to travel to Abu Simbel, a destination on the southern border, with a military convoy, and how they paid a random truck driver to transport them in the back of the truck. Victor, I, and the Englishmen wordlessly looked at each other and faintly smiled at the girls.

“Talking about unnecessary risks,” said the Englishmen to us, “India.” He paused for a long time. “Have you been?”

We shook our heads no.

“Oh, Egypt, even with the political climate now, is nothing compared to India. The poverty, the corruption, the rats, the dirt, or the dirt…” He talked about being at an Indian train station and seeing rats scrambling among people sleeping on the platform, about sub-human conditions of slum towns, seeing people defecate on streets…

“That sounds terrible!” One of the Ukrainian girls piped up.

“It was the hardest best trip I ever took. I wouldn’t trade those experiences for anything.” He said. And just like that – India appeared on our list.

Three years later, we were excitedly planning a 16-day trip around Northern and Central India. We have been to Asia once before, in Thailand, and were acutely aware of just how different India was going to be. Thailand was an excellent “Welcome to Asia” trip, a safe and friendly country, with great food, beautiful sights, and tons of travelers. It was exotic enough to entertain, yet innocuous enough to allow for very quick adjustment. Thailand made Asia seem “easy”. India was going to change all of that.

We tried to make it easy for ourselves by hiring a personal driver, instead of trying to brave public transportation. We planned out all our sightseeing stops and activities, we read up on the culture and history, and we met with an Indian friend for tips and inside scoops. We felt prepared. We weren’t.

We weren’t prepared for how really hard it was going to be. The second night after our arrival, we spent on a train, heading from Delhi to Udaipur. A thin black curtain separating our sleeping compartment from the corridor did nothing to isolate us from the noise, the lights, or the movement. People walking the corridor kept bumping into my feet, the train groaned and shook violently, as if it was about to derail, the air was humid and stale. Victor was getting a little sick, his temperature rising through the night. He moaned and tossed around on the upper bunk. I couldn’t sleep, listening to voices around me from other compartments crying, screaming, talking in a dissonance of languages. I’ve never felt another train lurch and shake like that and kept waiting for us to tumble off the rails into the foggy night. We have slept in less-than-ideal situations before. This was the first time that both of us wondered if it was worth it. At some point during the night, Victor later confided, he considered “hanging up his backpack and retiring from world travel.” By the morning, Victor’s temperature dropped back to normal, and we were in a new, never before explored city. Udaipur was a stunning start to our exploration of India, and the train terrors were quickly forgotten. Our spirits were on the rise, we thought we were over the worst of it. We weren’t.

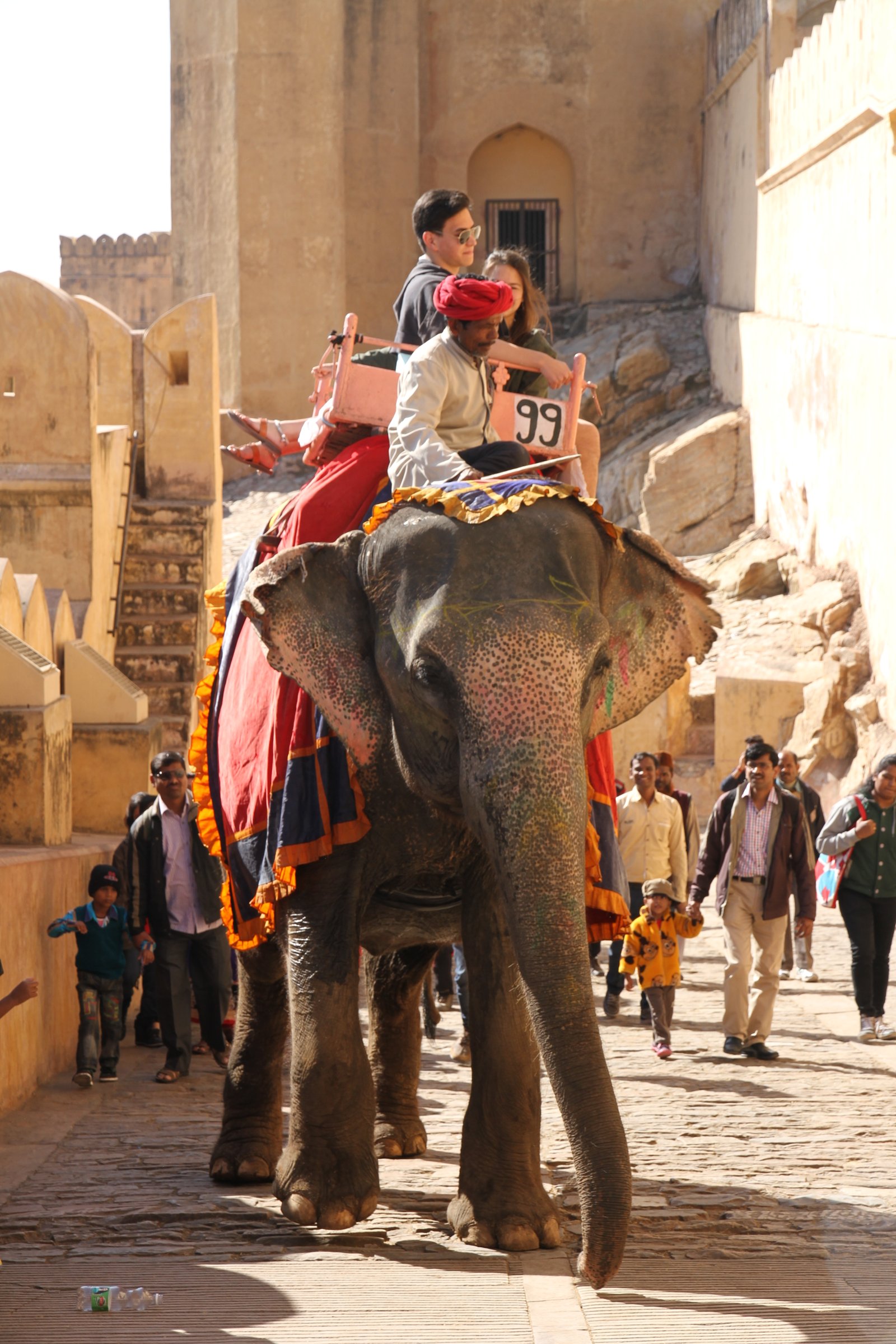

For every one of 16 days, India tested our resolve to travel and rewarded us for not giving up. We went from tasting the most delicious food to food poisoning. We saw the most extreme poverty and the most stunning architecture in one day. We weren’t prepared for the sheer number of people and animals, from buffalos to dogs, wandering the streets of Jaipur, much less the number of vehicles on the streets. One average traffic lane consisted of a truck, a car squeezing in right next to it, a tuk-tuk trying to zip past both, a motorcycle right next to the tuk-tuk, and a boy on a donkey basically in a ditch. We weren’t prepared for the cacophony of noise, the abundance of smells, and the ever-present garbage. I wasn’t prepared to basically walk into a man’s bathroom by simply walking on a sidewalk, suddenly being hit by a strong smell of urine, looking around, and finding a wall on the left of me being crowded with men’s urinals. Again, this was in the middle of a regular sidewalk. And still, it was less surprising than walking down a street, watching a woman ahead of us suddenly stop, pull up her long skirts, and release a stream of urine right on the ground. I had to hop around her, trying not to get sprinkles on my shoes. Victor wasn’t prepared to almost get trampled by a cow rounding the corner in Varanasi. One moment, we were turning the corner, the next moment, he had horns poking him in the stomach.

But the hardest part of the whole experience was how helpless this level and scale of poverty made me feel. There was no way to give money or food to a homeless child and not get immediately trampled by dozens of homeless children and adults. There was no way of feeding a starving puppy on a street because of the sheer number of roaming animals. Accepting that I couldn’t change anything around me and that I shouldn’t judge what was happening by my own standards was the first step in being able to start observing the environment, rather than emotionally responding to it.

The Englishman was right – it was the hardest best trip of our lives. So many things we experienced felt completely out of this world, it was impossible to classify whether each moment was mentally exhausting or spectacular. We climbed through the ruins of a beautiful temple with village children trailing in our footsteps. We watched dozens of volunteers chopping vegetables, boiling stews, and frying bread in an industrial-size kitchen to feed hundreds of worshippers in a Sikh temple. We sat, almost frozen in time, as the sun moved across the sky and set at the Taj Mahal, captivated by the changing of colors on the marble walls and by the magic that had this monument seemingly floating above the ground. We watched a village woman roll rotis directly on the dirt floor of her hut, fry them on an open fire, and hand them to us to taste. We saw corpses being burned in Varanasi and bones thrown in the Ganges River, as the morning mist set and chanting of prayers floated over the waters. We were not prepared for any of it.

Love it! Thinking of India and Tibet in the Spring 2020