I have never felt more lost in history and geography than on the streets of Sarajevo. Within the same block, there would be an old mosque, a Catholic church, an Orthodox church, and a synagogue thrown in for good measure. Strolling down Ferhadija Street, we would pass Viennese Secessionist buildings on one side, classical Ottoman architecture on the other, and an occasional Soviet-style block building, brightly painted to hide or possibly accentuate its modernist dreariness. There was an ancient Ottoman market selling hand-made copper coffee trays, mosaic lamps, and intricate Turkish rugs, one block away from luxury boutiques touting the latest brand names and Parisian-style cafes.

There are layers to Sarajevo, left by long-gone empires and political experiments. To walk its streets is to time-travel from the Ottoman Empire (1463–1878), to the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1878–1918), to Yugoslavia (1918–1992), while constantly reminding yourself that it’s 2025 and you are in Bosnia and Herzegovina. I can’t describe the whole city, but here are a few of my favorite places (and times) in Sarajevo.

In the heart of Sarajevo’s old Ottoman bazaar, meandering down narrow alleys among tiny shops, we constantly stopped to examine the gorgeous copper plates and coffee sets displayed in the windows. We weren’t planning on shopping, but the deeper we ventured into the bazaar, the more I realized that I couldn’t possibly live another day without a handmade copper plate. In fact, it seemed ridiculous that we have a perfectly good Turkish coffee set at home, but no plate to present it on. I promise I am not a shopaholic; I have no problems heading out empty-handed out of a Target or any other store, but bazaars and artisanal markets seem to easily break through all my defenses.

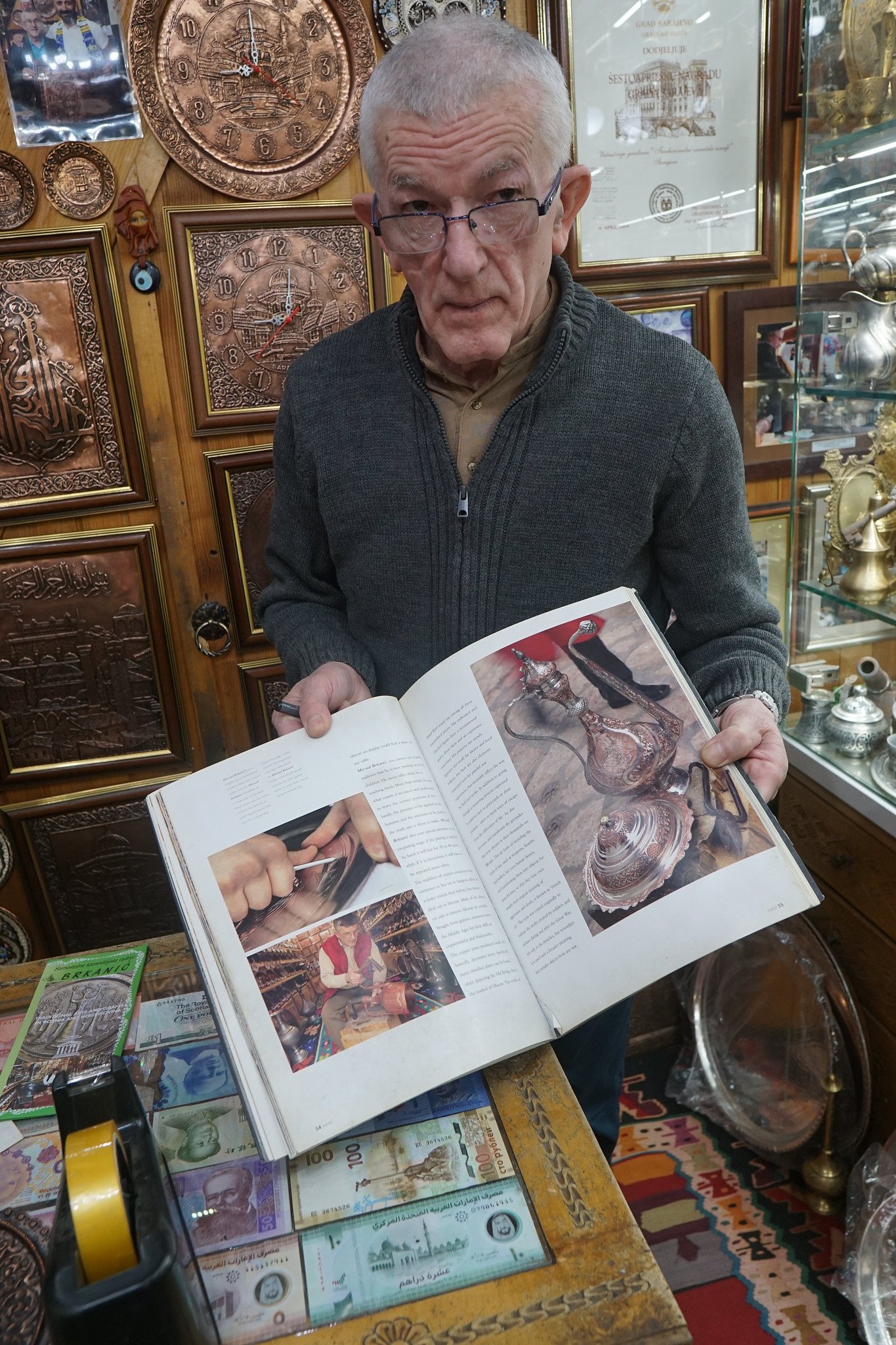

A craftsman in one of the stores showed us a UNESCO certification, pictures of Bill Clinton perusing his wares, told us he comes from a long line of coppersmiths and inherited this store from his father, who inherited it from his father, but most importantly, had the most stunning copper objects on display. We bought the plate of my dreams and not one, but two intricately decorated mini copper jugs. I don’t know how to explain any of this, so let’s just move on.

Just a short stroll away, we explored Gazi Husrev-bey Mosque, the largest in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and a beautiful example of Islamic architecture. Across the courtyard, I was fascinated with a clock tower, covered by unusual symbols, and clearly displaying… the wrong time. Turns out, Sarajevo Clock Tower is a lunar clock, and its mechanism is designed to show the time relative to sunset, which is when the Maghrib prayer is observed. So, the clock strikes 12 every day at the exact time of sunset and its primary function is to indicate the times for the five daily Muslim prayers. It is the only public clock still set to lunar time, a rare survival of an Ottoman tradition and must be manually adjusted twice a week to keep on ticking.

After strolling a few blocks, the wide streets, trams, symmetrical facades, and other indications of European urban planning, brought us out of the Ottoman Empire directly into the Austria-Hungary occupation. My favorite unexpected fact about Sarajevo was that it had the oldest electric tram system in Europe! It was built during a period of rapid urbanization when the city was transformed from an Ottoman provincial center into a modern European-style capital. Architecturally, the city exploded with Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Baroque, and Vienna Secession-style buildings — schools, post offices, hotels, and administrative buildings that still define its western half today. This progress did not please everyone, and while some welcomed modernization, others viewed it as cultural imperialism. The tensions between local identities and imperial ambitions eventually culminated in one of the most pivotal events of the 20th century: the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand by Sarajevo’s Latin Bridge.

It was there, outside what used to be a coffee shop and is now a museum, while standing in the bronze footsteps of Archduke Ferdinand, that the historical significance of Sarajevo seemed to make its final impression on me. I have heard the story before - the missed grenade, the wrong turn, and the fatal encounter that triggered World War I, but being at that place, at that moment, suddenly made it real. It was here that one bullet marked the beginning of the end for the Austria-Hungarian Empire.

And just across the river, we finally came face-to-face with Yugoslav modernist architecture in the form of the ugliest building in the whole of Sarajevo. Zgrada Papagajka (literally “The Parrot Building”) is a heavy concrete structure, decorated with bright vertical strips of red, blue, yellow, and green, further accentuated by cracked and peeling paint and occasional graffiti. It was built in the 1980s, during a major socialist urban development push in Sarajevo, as the city prepared for modernization ahead of hosting the 1984 Winter Olympics. It’s a startling example of Yugoslav-era architecture, in the sense that I was certainly startled when I first saw it. The residents, it seems, do find it ugly, but have embraced it as a symbol of their beloved city’s eclectic nature. The more I saw it, the more it grew on me as well. By my last day in Sarajevo, I looked forward to spotting it across the river.

Each corner of the city felt like it belonged to a different world, and yet somehow, it all came together in a single, cohesive whole, as we strolled from one end of the city to the other. It made sense, it belonged together, and it was wholly unique. There is a thing that I do sometimes in new places: pretend I have no idea where I am and try to figure out the country by clues around me. I can confidently confirm that I would have certainly guessed Europe, but would have never narrowed it down to Bosnia. But the thing about Sarajevo is if you visited it even once, you could never confuse it for another city.

Not for the first time in my travels, I wondered what it would be like to live in a city I was briefly visiting – always a clear sign that I am falling in love with the place. Sarajevo struck me as endlessly complex yet instantly welcoming, a city that wears its history on every wall and makes you wonder about its future. I don’t know if I will ever live here, but I do want to come back, even if it is just to see what’s next for Sarajevo. And definitely to eat another burek.

Coming up: Don’t call it a burek. It’s complicated. Bosnian Food Post.