“You enter on the right through the dragon door and exit on the left through the tiger door. And you never enter or exit through the middle door. That door is for gods.”

We sat on a bench in front of a brightly colored Taoist temple with a rooftop looking like something made from LEGO pieces, reading up on Taoism and temple etiquette.

Years ago, we visited Taoist temples in Beijing and even learned a little bit about this ancient Chinese philosophical and religious tradition, but the Taiwanese places of worship were different—more vibrant, whimsical, and with more intricate details. By the end of our time in Taiwan, Taoism was still largely a mystery to us, but some elements of temples and rituals became a little bit more familiar.

On the first night in Taipei, we stopped by a temple near the popular Shilin Night Market. The temple was filled with decorations, statues of deities dressed in colorful garb, and freshly cut flowers. Food items were generously spread out on the offering table with unmistakably Chinese red lanterns hanging from the ceiling. Near the altar, we saw an elderly woman praying. She muttered her prayers, bowed, and then tossed two red wooden pieces onto the floor. She briefly examined them, picked them up, and threw them on the floor again. Then again and again. We had no idea what was happening, but we were intrigued by this ritual.

The next morning, we headed to Lungshan Temple—one of the main shrines in the city. The place was busy: locals, tourists, and even schoolchildren brought on school buses crowded the temple’s courtyard. And, it seemed, everyone—old and young—wanted to throw red wooden pieces onto the floor. In the back, an old man showed the mechanics of the ritual to those who were not sure what to do.

If we got it correctly, it works something like this: the red, crescent-shaped wooden pieces are called jiaobei (筊杯) and used as tools for communicating with the gods and for getting yes/no answers regarding important life questions. Each jiaobei block has a flat side (yang) and a curved side (yin), and you toss them in pairs on the floor. The answer to your question depends on how these pieces land. If you get a combination of a flat side and a curved side, the answer is “yes”. If both blocks land with the curved side down, the answer is “no”. If both end up as flat side up, it means that the gods are laughing, and your question is deemed irrelevant.

In Lungshan Temple (and many other temples around Taiwan), there was also a bucket of wooden fortune sticks with numbers. You hold a fortune stick and toss jiaobei on the floor, and if you don’t get a “yes” answer, you need to draw another stick with a different number and drop the wooden pieces again. Once you get a “yes”, your lucky number is the number on the stick you are holding, and you can get a message about your future from the nearby box. The practice reminded us of what we saw people doing in Japanese Shinto temples.

I dropped jiaobei several times, and each time they landed incorrectly, both sides were either up or down. I tried again and again, taking a new fortune stick after each unsuccessful attempt. Finally, it worked. The wooden pieces landed properly while I was holding a fortune stick with the number 68. The old man satisfactorily nodded and motioned us towards the box in the corner. I opened drawer No. 68 and took a piece of paper with Chinese characters.

“So, what’s the message? What does my future hold?”

Julia pointed her iPhone using the Google Translate app, and the first two words on the screen were “court” and “litigation”.

“What?!!” I nearly burst out laughing. “How does it know that I’m a lawyer and do litigation?”

“It means your vacation will be over soon, and you’ll go back to work,” Julia commented with a laugh. The rest of the card mentioned something about transactions that will follow and “bring wealth and prosperity in spring.” Please check with me in a couple of months to see if the transactions have indeed followed.

The city with the most Taoist temples that we visited was, without a doubt, Tainan. For many people, the first capital of Taiwan is now known as a place of many temples and as a foodie destination. Taoist shrines here compete with delicious food joints on nearly every corner. It feels like people in Tainan are born to eat and pray and then eat and pray more. And this is not an embellishment by a travel writer. That’s just how it is.

We visited so many shrines in Tainan that we lost count of how many of them we’ve poked our noses in. One evening, we even got caught in a religious festival by one of the temples. High-paced, coordinated dragon dances, people dressed in character costumes performing rituals, and girls in traditional clothes swirling in front of the temple to the sounds of drums—the celebrations were colorful and mesmerizing, and captivated us for hours. We had to leave the festivities only when our hungry stomachs demanded the advertised delicious Tainan street food from a night market.

But what I will remember the most about Tainan is what happened on Monday, December 21, 2025. That morning (in Chicago, it was still the preceding Sunday night), the Chicago Bears hosted the Green Bay Packers in a pivotal divisional matchup. I couldn’t watch the game, but I wanted to help my team from afar. At breakfast, I suggested to Julia that we head to a temple, pray for the Bears, and burn fake money to generate luck as customary at Chinese temples. Initially, I suggested this as a joke, but Julia loved the idea, and after the meal at the local market, we were on our way to appease the gods.

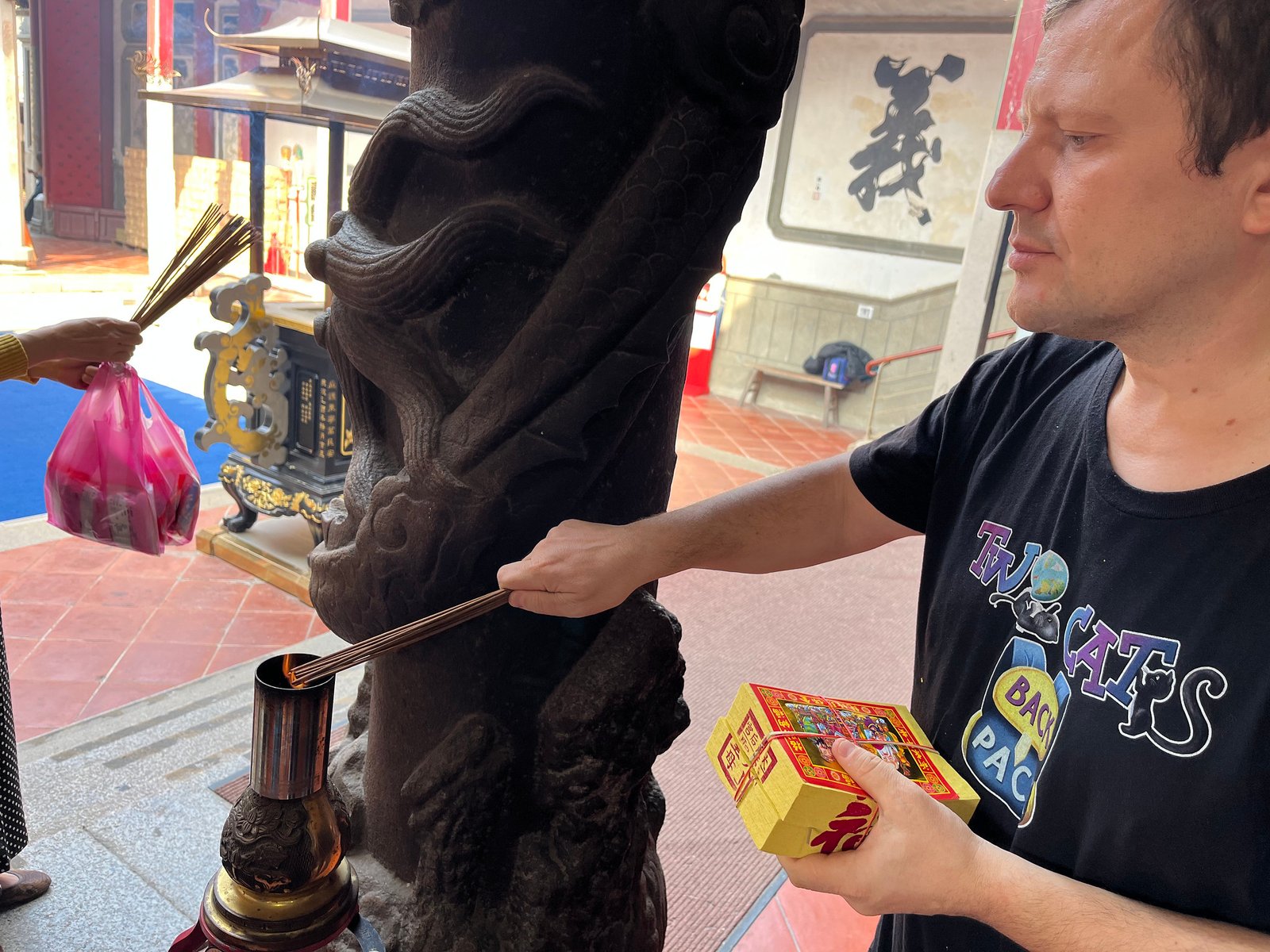

The practice of burning fake money, also known as joss paper, is a common practice in Taiwan. Nearly every temple had mounds of fake money for sale and a furnace where you could burn it. We often saw people folding joss paper in half and burning it for luck. We approached the Grand Mazu Temple. The score on my phone flashed: the Bears were down by ten in the fourth. They needed my prayers.

At the temple, we paid 100 Taiwanese Dollars (around USD $3) and received ten incense sticks, a packaged food offering, and a stack of joss paper. As the game clock was winding down and the Bears were still trailing, we frantically started to look for the furnace but couldn’t find one. This was one of the largest temples in town, and the incinerator was not easily located. As we ran around the temple’s halls and courtyards, my anxiety started to set in. I feared that the game clock would expire and the Bears would lose the game with me clutching joss paper like Matt Eberflus holding on that final timeout one year ago.

Finally, we found the furnace. But then, another problem—I suddenly got cold feet.

“What if I’m offending the locals and their religion?” I mumbled. “I’m not a Taoist. This doesn’t feel right.”

Julia had to immediately intervene to assure me that I was not offending anyone, and it was perfectly fine for me to pray for the Bears’ win.

“Remember in China we saw parents praying at a temple for their child to get into Brown University. It’s OK! Now get in the line.”

I joined the line. The fake yellow money in my hands was almost the same color as the Packers' green and gold. When it was my turn, I folded it in half, whispered “Bear Down,” and threw the paper in. It caught the flames and burned beautifully. I folded more fake money and put it in. The locals lined up behind me, and I saw their fascination and no judgment whatsoever.

When I was done, the Bears were still down by ten with less than five minutes to play.

And then. The most improbable comeback happened.

The Bears scored a field goal, and then, against all odds, recovered an onside kick and scored again in the dying seconds of the regulation. The game went in OT, where Caleb Williams threw a game-winning touchdown, sending the packed and cold Soldier Field into a frenzy, and another true believer thousands of miles away into a wild celebration outside of the temple walls.

The score on my phone showed: Bears-Packers 22:16.

I jumped into the air and screamed in jubilation.

A true miracle and a divine intervention.

Taoist temples were one of the highlights during our trip. Full of vibrancy, color, and intriguing traditions, they were not like anything else. The sound of jiaobei hitting the floor followed us from town to town and was so ubiquitous that it became almost an unofficial soundtrack of Taiwan.

We returned home full of memories, and the only question I still have is whether we should have found any Taoist temple in Chicago and burned some fake money before the Bears-Rams playoff game. The Bears lost that close game, and who knows—maybe a prayer to Taoist gods would have changed the final score.