After the fire at the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris earlier this year, I saw many people on social media lamenting that they hadn't had the chance to see Notre Dame before it was badly damaged. The lesson, of course, is that we should live in the present and not put off visiting special places. In 2015, we arrived in São Paulo, Brazil, just days after a fire severely damaged the Museum of the Portuguese Language, and all we got to see were the charred remains of the roof and walls of the building.

But sometimes, catastrophic events give places a fresh start. Two of my homes, Chicago and Minsk, are good examples. Both cities have been almost destroyed in the past. Most of Chicago was devastated during the infamous 1871 Fire. The tragic event provided the city with a chance to rebuild from a clean slate and become home to the first skyscraper in the world and a mecca of American modernist architecture. It's unlikely that Chicago would be boasting its current architecture if the old Chicago with its crooked streets and lack of alleyways remained intact.

Minsk, the capital of Belarus and my hometown, was destroyed by the Nazi Germans during World War II. When it was liberated in July 1944, all that remained was a pile of smoldering rubble with only a handful of buildings standing. After the war, the city was rebuilt. Minsk’s architecture is an interesting subject. Some visitors find it repulsive, and I've heard such adjectives as “ugly” and “Communist” thrown about. But if you want to see the best examples of grand Stalinist architecture, Minsk is the place to visit.

And this is why I found our visit to Rotterdam so fascinating. Like Minsk, it was leveled by the Nazis. In a matter of one day, the Luftwaffe pilots turned the old European port city into a pile of rubble. Yet, Rotterdam used this terrible chapter in its history to get a fresh start and rebuild. In a sense, it became a Chicago of Europe. A walking tour of the city reveals the full extent of post-war creativity. Unlike Minsk—which was under Communist rule for nearly 50 years after liberation and where all creativity was hampered by the strict norms of Communist architecture—Rotterdam is a city in the free-spirited Netherlands, providing outlets for creativity to various architects. The entire city is an excellent primer of European modernist architecture.

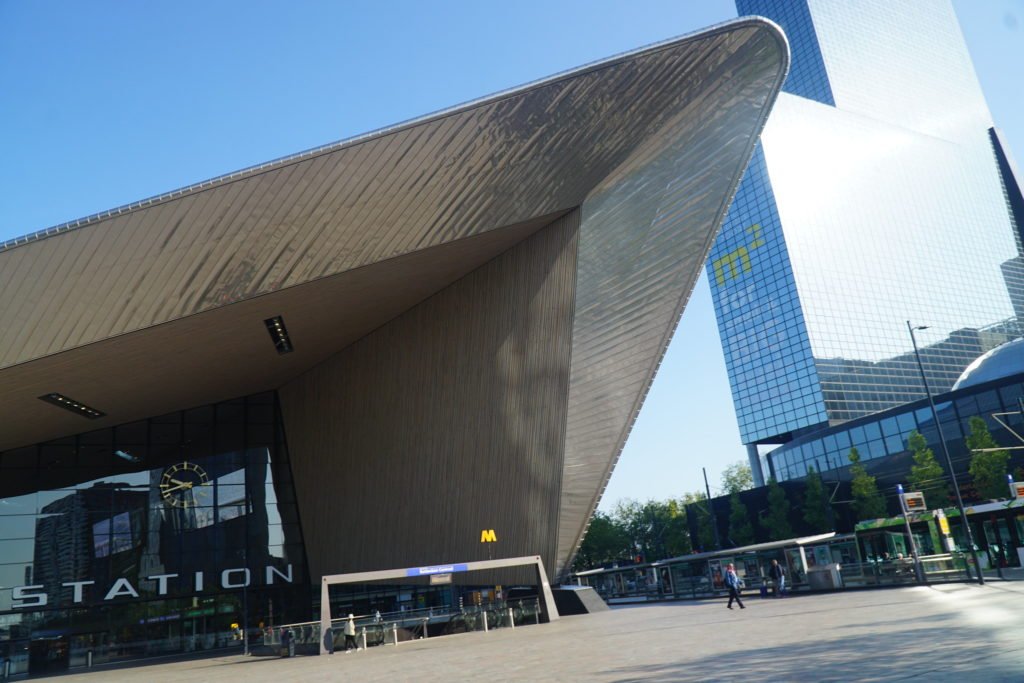

Taking a break from visiting quaint Dutch towns, such as Delft, Leiden, and Haarlem, we spent a day in Rotterdam, and it dazzled us with its unusual and imaginative architecture. Arriving from Delft on a train, we started our exploration at the sleek-looking train station. If you stand outside and don't know what you're looking at, you may think that the building houses the European Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame, as the facade looks like a tilted angle of an electric guitar suspended in the air. Right next to it, competing for weirdness is a modern-looking St. Paul’s church (Pauluskerk) that looks more like a fashion boutique than a church. If God does exist, he (or she) wears Prada.

Walking just a few blocks from the train station, it became immediately clear to us that buildings in Rotterdam are anything but boring, with even the most trivial residential apartment complexes having their quirks.

Speaking of unusual residential architecture, the most bizarre residential development in Rotterdam is the infamous Cube Houses (Kubuswoningen). Designed by Dutch architect Piet Blom in 1977, these 39 yellow cube homes are tilted by 55 degrees. The rows of these sunflower-looking homes create an impression of cubes thrown and frozen in midair, threatening to fall on pedestrians. As we were outside looking at this weird housing project, we wondered: how do you live inside? Is it even comfortable there? To find answers and decide for ourselves, we went inside one of such cubes—the Show Cube Museum. The cubes do look livable inside. However, there is plenty of space wasted to level the 55-degree tilt. Also, living in a place like this, one can forget about buying furniture from IKEA, as everything needs to be customized.

The nearby buildings are just as strange. Right next to the Cube Houses is another radical project by Piet Blom—the Blaaktoren (1984)—a residential tower known as the “Pencil” due to its pointy top. Its neighbor, the industrial-looking building with yellow pipes, is actually the city’s central library. Yet, this area is dominated by an imposing Markthal. This giant horseshoe-shaped building is not your average market hall. It was created by the leading Dutch firm MVRDV and inaugurated by the Dutch Queen in 2014. Inside, one can find a bustling covered market selling everything from Dutch cheese to pickled herring. The building also has hundreds of offices and apartments, though their existence is not immediately obvious to visitors. The entire inner ceiling is adorned with one of the largest artworks in the world, the Horn of Plenty (Hoorn des Overvloeds), composed of giant fruits and vegetables floating through the air above.

Rotterdam is one of the largest and most important European port cities. Unsurprisingly, the city’s waterways are also graced by contemporary architecture. One of the iconic structures is the Erasmus Bridge connecting the northern and southern banks of the Nieuwe Maas. The locals call it the Swan due to its unique design resembling a large, elegant bird. Also by the river is a building with a roof that resembles a giant diving board. And of course, one of the largest buildings along the river is De Rotterdam. This enormous building creates an impression of three separate buildings, yet it's a single entity. The top looks like three dislocated and hanging blocks, threatening to tumble off into the river. As with the Cube homes and many other buildings in Rotterdam, architects here like to play with the concept of imbalance, creating an impression of disjointed and strangely connected parts of the building. Some may also find that the innovative touch of De Rotterdam is manifested in the building’s unusual resemblance to a ship with three giant sails. Given Rotterdam’s importance as a port city, such symbolism cannot be lost on any visitor.

If Rotterdam hadn't suffered war destruction, it surely would have looked very different today. Out of the ashes of World War II, with a renewed spirit of modernist creativity, a brand-new Rotterdam sprang into place and will continue its experiments with innovative architecture long into the future. I find great comfort in the resilience of the human spirit in both my hometowns and my travels.